Innlent

Erlent

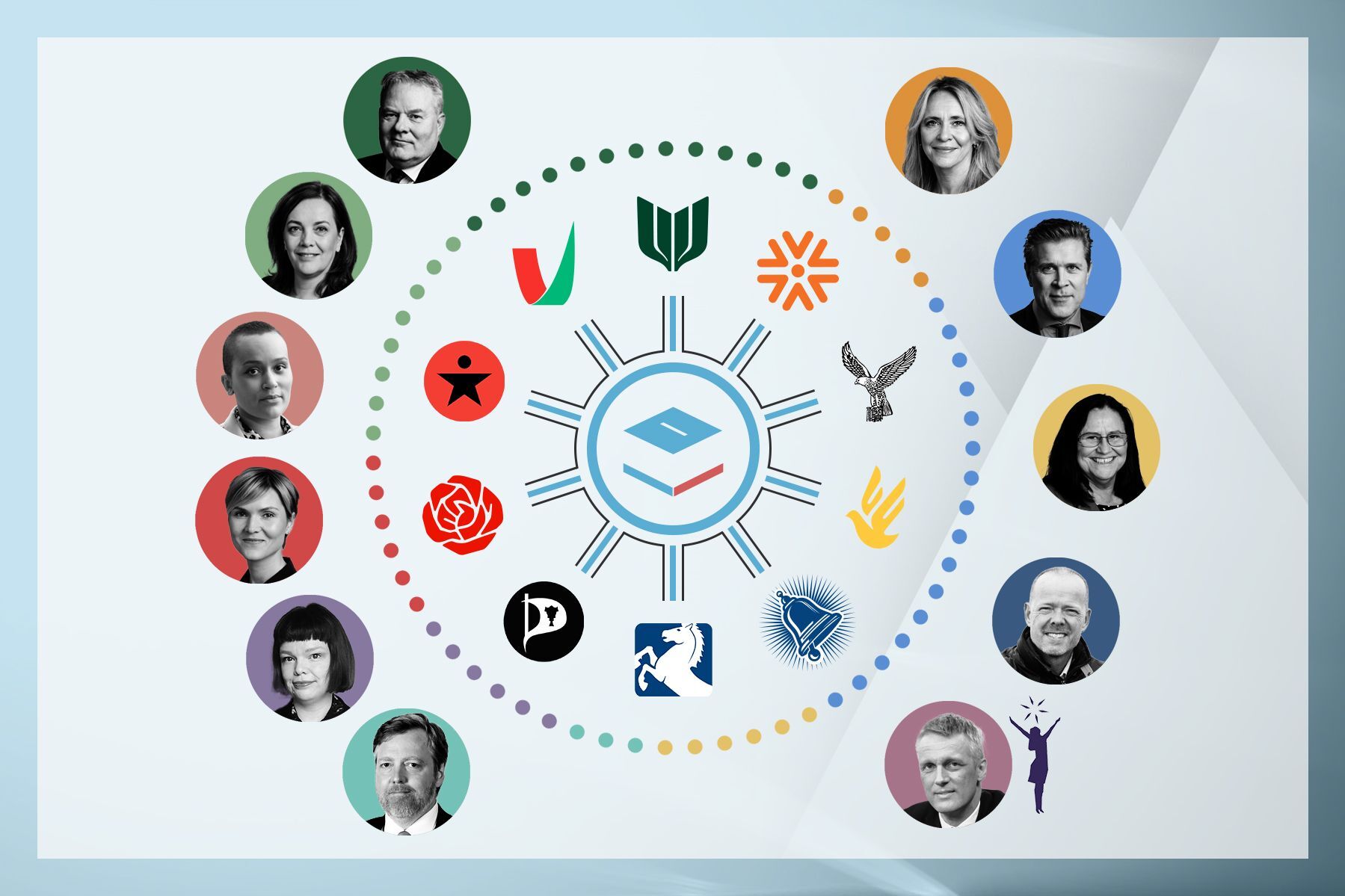

Kosningar 2024

Veður

Hádegisfréttir

Kvöldfréttir

Stjórnmál

Reykjaneseldar

Donald Trump

Dómsmál

Andlát

Samtalið

Pallborðið

Kompás

Innlent

Erlent

Atvinnulíf

Neytendur

Kauphöllin

Seðlabankinn

Vistaskipti

Veitingastaðir

Samstarf

Fréttir af flugi

Fasteignamarkaður

Ferðaþjónusta

Staðan í deildum

Fótbolti

Körfubolti

Handbolti

Besta karla

Besta kvenna

Bónus karla

Bónus kvenna

Enski boltinn

Olís karla

Olís kvenna

NFL

Íslenski boltinn

Meistaradeildin

Golf

Rafíþróttir